- Introduction

The legal industry is in need of ideas for change and innovation, and I found just the person to look to.

Elon Musk is the founder of SpaceX, and the co-founder of Tesla Motors and SolarCity.

With SpaceX, his goal is to make humans a multi-planetary species. In Tesla, his vision, dubbed the ‘Master Plan,’ involves creating a fully electric car that is affordable and can be manufactured at high volumes. Using SolarCity, he plans to create low-cost sustainable energy by harnessing the power of the Sun.

Before that, he was the founder of Zip2 and Paypal. The former was a software company that designed online city guides, and the latter is an electronic online payment platform.

He is the closest thing to a real life Tony Stark that lives in our time.

So how does a man who started his career in software engineering end up being at the forefront in aerospace, automotive, and solar energy? There are many things that lawyers and law students can learn from a man that is attempting to change the landscape of 3 gigantic industries.

Here I have offered 2:

- First Principles Reasoning; and

- Learning Transfer

- First Principles Reasoning

Musk describes that one of his core philosophies that guides his method of thinking is called First Principles reasoning.

First Principles, Musk describes, is a physics way of looking at the world. You boil things down to its most fundamental principles, stripping away all the assumptions that we have accumulated about the topic, and then reason up from there.

He gives an example of a battery pack in an electric car. Historically, a battery pack costs $600 per kilowatt hour. The assumption is that battery packs are expensive. As a car manufacturer, you take that assumption as an unchangeable fact and figured you will just have to integrate that cost into the price of the car.

With first principles, a person would attack that assumption. You boil the battery pack down to its fundamental principles and look at what are the material constituents of the battery, how much those materials would cost, and how much it would cost to assemble them into a battery. If you realize that it will actually only cost you $80 per kilowatt hour, you have now changed what everyone else took for as a fact.

As law students and lawyers, our challenge is to identify the assumptions built into our legal industry that we had accepted as fact over time.

For example, take the cost of legal services. In a 2015 Canadian Lawyer legal fees survey, the average hourly rate of a 10-year call was $360 per hour, and the national average cost of a 5-day trial is $56,439. The assumption is that legal services are expensive, have always been expensive, and will always be expensive.

Let’s take a first principles approach. Attack that assumption. Boil down the cost to its fundamental parts, and take a look at what components are no longer needed or can be changed.

Take a look at what Axiom Legal did. It realized that a big law firm with a large beautiful office space that is located in a prime location garners prestige, but also attracts a massive overhead. Instead, Axiom has its employees working remotely or onsite with their clients, and the result was that Axiom was able to eliminate 30 percent of a traditional firm’s overhead.

Another example is the billable hour. Lawyers have been using the billable hour to charge their clients because it is simple, familiar, and is flexible enough to account for the varying times it can take to work on a file. The assumption is that the billable hour is the best way to charge clients because no better method exists. However, the billable hour is unpredictable for clients because they do not know how much they will be billed for, and this allocates the risk to them.

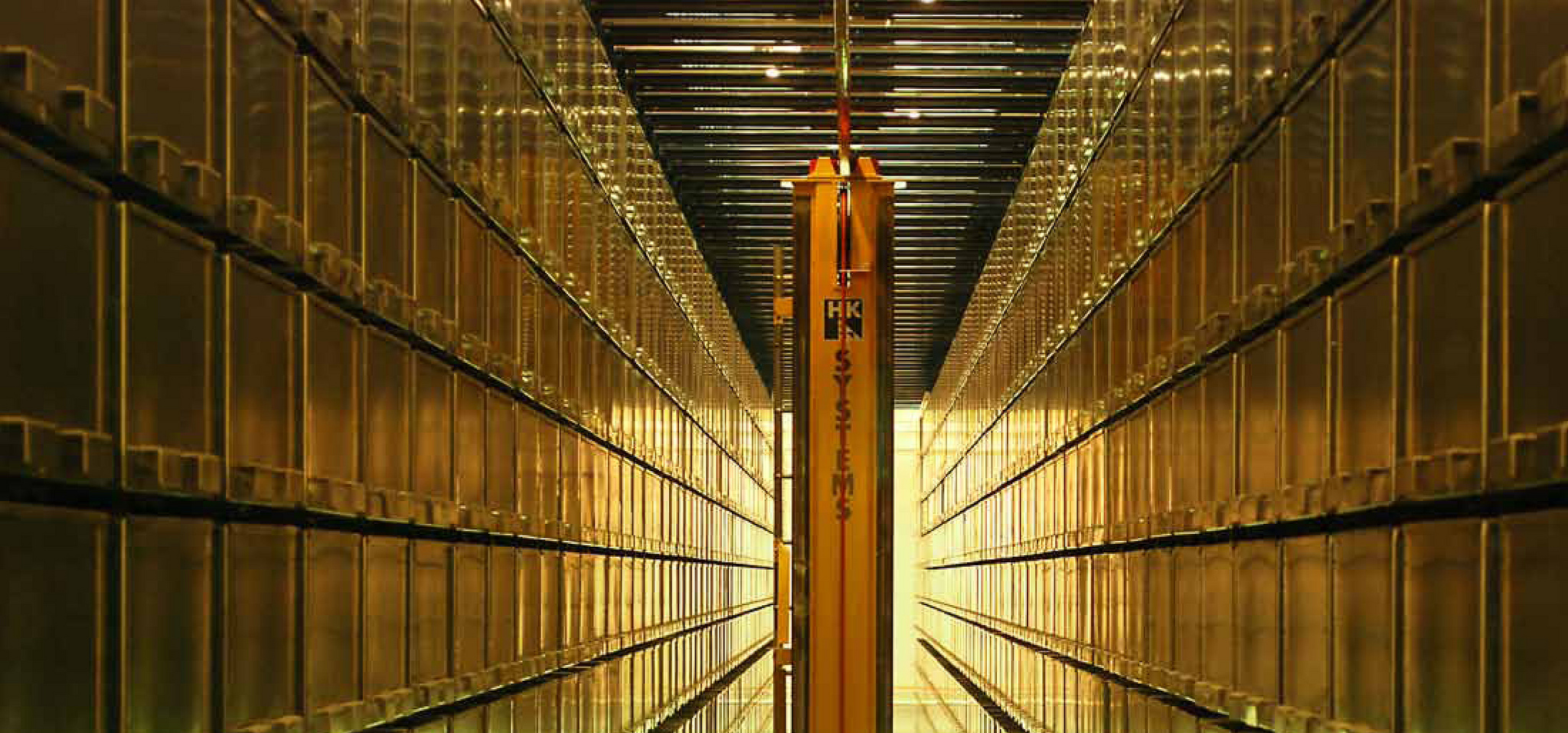

Let’s look at how Hughes Amys LLP has attacked this assumption. Hughes Amys employs an alternative fee arrangement. They use a practice management software to gather data on personal injury files. They looked at the average costs for different claims, the average times it took for these claims to be resolved, and the average awards that were paid out. The firm then presents this data to the client to provide a transparent estimate of how much a flat fee for the month would cost.

What other assumptions should we tackle?

- Learning transfer

Elon Musk has become a leader in many areas of industry such as space exploration, automotive and energy. He is also a leader in many areas of their technology including reusable rockets, self-driving cars, and residential solar roofs.

One of the reasons he is so competent in these different areas is because he is very proficient in Learning Transfer. Learning Transfer is a process where you transfer what you learned in one context and apply it to another.

Elon Musk is an avid reader and eager learner. According to his brother Kimbal Musk, Elon would read 2 books a day. The books he reads spans multiple disciplines and interest areas, including philosophy, religion, programming, and science fiction. He would also read the biographies of influential figures such as Benjamin Franklin, Albert Einstein, J.E. Gordon, and Howard Hughes.

Musk then uses what he learns in one industry and applies it to another. Combined with the first principles approach, Musk would deconstruct a field of study into its fundamental principles, compare and contrast these principles with a second field of study, then reconstruct the lessons learned from the first to the second. He has done this to quickly become proficient in the field of artificial intelligence, physics and engineering.

As lawyers and law students, how can we apply learning transfer in our practice?

In an essay written by Ben Heineman, William Lee, and David Wilkins titled “Lawyers as Professionals and as Citizens: Key Roles and Responsibilities in the 21st Century,” the essay urges lawyers and students to develop complementary competencies in addition to our core competencies.

Our core competencies are things like our basic legal training on the main legal subjects such as contracts, torts and property. It also includes legal skills such as critical thinking, analysis, and issue-spotting.

However, with new technology such as the artificial intelligence lawyer ‘ROSS’ that can do legal research on an entire body of law faster than what a human can achieve, including legislation, case law and secondary sources, the contemporary lawyer must possess inter-disciplinary knowledge and skills in order to stay competitive in the market.

This is where learning transfer can be useful in developing our complementary competencies. Complementary competencies are things like cost-benefit analysis, creative and constructive thinking, risk management, negotiation, communication, and value-based decision-making.

For example, one of the core competencies we develop in law school is issue-spotting. During an exam we are given a fact pattern and, drawing from the topics we’ve learned in that class, we can determine what legal issues need to be analyzed in that question.

Now let’s use learning transfer to apply that skill set to another context: negotiations. The fundamental principle in issue-spotting is being able to identify the ‘triggers’ in the fact pattern that tell you what legal rules will be engaged. You can transfer that fundamental principle to negotiations by learning to identify the key information in each negotiating party to determine how much bargaining power each party possesses.

As a student trying to become a 21st century lawyer, who better to learn from than the 21st Century Industrialist? There we go, we got a little bit of learning transfer going on right there.

- Conclusion

The legal industry is notorious for being very conservative. Clients want more value for their money, and new technological advances are threatening the old ways of doing things. Elon Musk is trying to break the status quo in 3 very large industries, and we can learn a lot from him.

As law students and future lawyers, we have the controls to choose the direction our profession takes in the coming years. It’s easy for us to be resistant to change and be protective. After all, it feels personal to us because it is our livelihood. However, this is an excellent opportunity for us to be at the forefont in changing how lawyers do their jobs.

Or … we could be like Comcast to Google Fiber and bury our heads in the sand. The choice is ours.