Why you need to know about Black Swans

The first encounter:

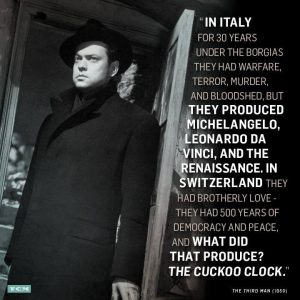

In 1697, Dutch merchant, William De Velaming, became the first European ever to set eyes on a black Swan while sailing the western coast of Australia. Before this point, no one in Europe had ever heard of a black swan, and its “discovery” sent shockwaves across Europe. The bird left such a lasting mark on the European psyche that three centuries later, the term “Black Swan” has been borrowed to refer to unforeseen and consequentially disruptive events.

Instances of black swans vary from time to time and are spread out through human history. The key feature to remember is that black swans arise out of an inherent psychological bias that humans share against outlier events.

For example, after the First World War, French military engineers constructed fortified trenches that stretched for miles across the French-German border. In their wisdom, the French engineers had envisioned a defensive position that would thwart a future invading force.

The “Maginot Line” was France’s perfect response to a future German invasion, except that the Second World War was not fought in trenches. Innovative battle techniques (i.e. Blitzkrieg) and new technologies of mass destruction transformed the line from a miracle of engineering to a giant ditch of concrete.

But what went wrong?

In his book, The Black Swan, Nassim Taleb tells the story of a turkey that is fed and kept fat by its farmer. This ritual goes on for a thousand days until the Turkey associates each new day with a fresh supply of food.

On the 1001st day, the farmer slaughters the turkey and feeds it to his family. The turkey has a Black Swan moment.

In hindsight, the turkey’s predicament is perfectly foreseeable. The farmer feeds the turkey because he wants to slaughter it at a future date. However, to the unsuspecting turkey, the pattern of being fed is never broken and so there is little reason to think otherwise. The logical choice for the turkey is to continue eating because the supply of food appears infinite.

A real-life example to the turkey parable is the 2008 Financial Crisis. Prior to the crash, sub-prime loans and mortgage-backed securities were highly favored by lenders and credit agencies alike. In fact, mortgage-backed securities were first introduced in the 1970s as a measure to hasten economic growth and stimulate real-estate purchases. However, it was only after the crash that the rhetoric surrounding their use became highly negative. The financial industry experienced its own black swan moment; it innovated to eat more.

The “Progress Trap”

A theory blames the giant statues on Easter Island for the death of the Island’s inhabitants.

It goes like this: the inhabitants of the island perceived the statues as the highest mark of divine favour. They cleared out vast amounts of land and cut down thousands of trees to erect more and more of them. The process became the ultimate purpose of the Island’s inhabitants.

The building frenzy went on until the Island’s fragile ecosystem collapsed and wiped out the island’s inhabitants. They were not slaughtered by a farmer, but died due to famine and a shortage of food.

A first-year student may refer to this as a “tragedy of the commons”, but there is more to it than just that.

The islanders triggered a “progress trap”. They became victims of their success. For them, the process of building became a synonym for economic output and progress. They even came up with innovative new ways to deforest the land and destroy the very foundations of their habitation.

Looking back, it’s easy to blame them for their demise, how could they not see it? However, for the islanders, their ultimate doom was nothing short of a Black Swan.

“to the unsuspecting turkey, the pattern of being fed is never broken and so there is little reason to think otherwise”

—

We live in an era where an interconnected world is increasingly susceptible to Black Swan moments. Each day, disruptive technologies are transforming the world in which we live.

The legal profession is not immune to these external forces. Our ability to provide legal services is no longer an infinite resource. Each day, lawyers face increasing competition from alternative service providers and digital

cyber platforms (the internet). The threat of artificial intelligence is looming over the profession.

And yet the level of innovation within the legal profession remains stationary. In the past 100 years, the legal profession’s greatest innovative measure is a set of business management principles by Paul Cravath – an innovative approach if the underlying objective is to “eat more”.

This is not to say that firms have stopped innovating. Large firms possess modern IT departments and tend to purchase the latest technology to streamline their internal processes. However, are these initiatives fundamental to transforming the legal profession? Alternatively, do they simply make lawyers more susceptible to a “progress trap”? It is difficult to say.

Large law firms have been able to avoid failure by expanding their client base and downsizing inefficient departments by pursuing austerity. But, post-2008, the demand for legal services is declining. The current 1-2% annual growth figure is highly reliant on macro/global economic trends, such as quantitative easing (printing of money) and population growth. In other words, the legal profession may be waking up one day to a farmer holding an axe.

“The legal profession is not immune to these external forces.”

—

Why Does Access to Justice Matter?

The contemporary access to justice crisis serves as the perfect moment for self-reflection. Somewhere along the road, profit generation became the main focus of the profession while the delivery of legal services shifted to become only a secondary consideration. Most lawyers would agree that access to justice is a serious issue, but there has been little political will to change the profession fundamentally.

In today’s terms, becoming a lawyer isn’t just being part of an esteemed profession, but it is also a relatively reasonable investment. This makes lawyers weary of any drastic changes to the profit-making dynamics of the profession. Meanwhile, people of lower socio-economic background and those living in rural communities are more and more in pursuit of alternatives.

This makes innovative measures aimed at solving issues of access to justice imperative to the future well-being of the profession. Access to justice isn’t just a trendy phrase, but also key to reshaping the delivery of legal services. It is important because it introduces a non-profit, service-oriented perspective to the profession.

Nassim Taleb once said that our goal as a society shouldn’t be to predict Black Swans but to adjust to their existence. The logic of black swan suggests that “what we don’t know is far more important than what we do know”. The mere consideration of outlier events in our macro decisions could reduce their force when they do take place.

This fact alone should encourage the legal profession to encourage more innovative solutions, solutions that go beyond streamlining the process and instead raise fundamental questions as to the nature of the profession.

I am not a rural lawyer (yet), but I have developed a great deal of experience working in our family law office, running my own registry business, and being involved in our community. I have also had opportunities to speak with a variety of lawyers, about their professional experiences.

I am not a rural lawyer (yet), but I have developed a great deal of experience working in our family law office, running my own registry business, and being involved in our community. I have also had opportunities to speak with a variety of lawyers, about their professional experiences. beautiful sunrise and four moose in our field. I thought, “This is already going to be good”.

beautiful sunrise and four moose in our field. I thought, “This is already going to be good”.

In the afternoon, we drove to court in Calgary on an interesting estate matter. We usually travel to court in Didsbury, Airdrie, Red Deer, Calgary, and sometimes Edmonton.

In the afternoon, we drove to court in Calgary on an interesting estate matter. We usually travel to court in Didsbury, Airdrie, Red Deer, Calgary, and sometimes Edmonton.